The Memory Police: Orwellian? Kafkaesque? Or a secret third thing?

A review of 'The Memory Police' by Yoko Ogawa and a nudge to start a workplace book club

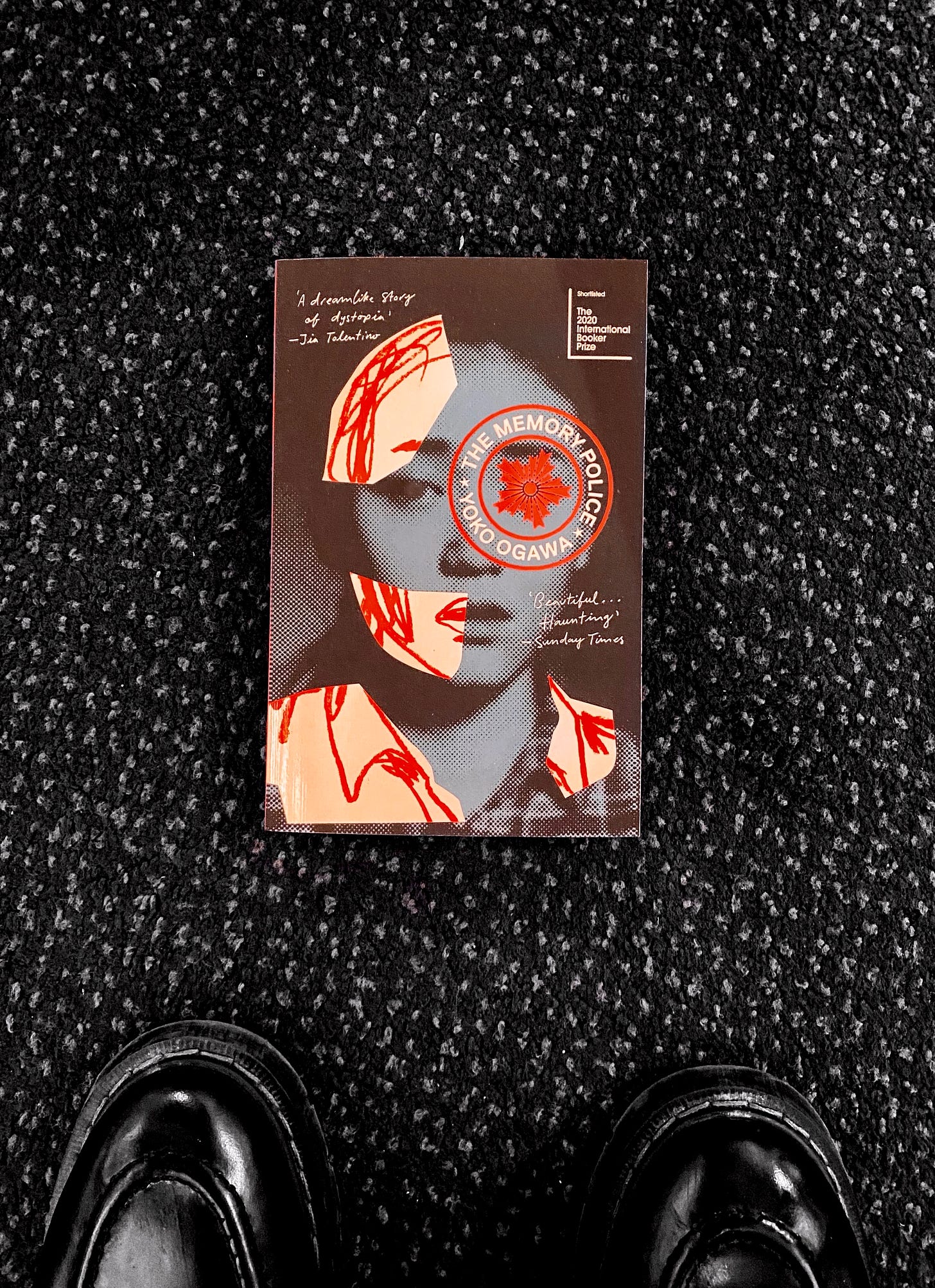

This novel was our June book club pick at work. It’s Booker-shortlisted, features a deeply unreliable narrator, and layers ambiguity upon ambiguity; a recipe for a great discussion!

Most of our deliberations centred around the unknown or missing parts of this story. We found it unsettling to never find out how the island came to be under the oversight of the Memory Police and to have no explanation for how the disappearances are chosen. On top of this, those who are able to hold onto their memories don’t do much with them. There’s a sense of futility to the act of intentional remembering and the resistance movement isn’t spoken about in much detail. As readers, we’re left searching for voices on an island determined to silence the voice in all its forms; on the page, in dialogue, and within the mind.

Interestingly, we were quite divided on whether the book should be characterised as Orwellian or Kafkaesque. The characters’ forced emotional isolation but desperate desire for closeness is very reminiscent of 1984, but the resigned incomprehension of how the state operates points toward The Castle. There’s total subservience to the state (Orwellian), unnamed characters who aren’t certain why they’re on the run (Kafkaesque), citizens surveilling each other (Orwellian), and faceless men who uphold the rules without question (Kafkaesque).

To me, whether its written in the Orwellian or Kafkaesque traditions, this book is about the totality of totalitarianism. The sheer be-all end-all of it – the memory loss, the nonexistence of privacy, the futility of resistance – kept coming up for me as I read. Ogawa’s prose has a very specific aim and I think this is it; she wants us to be totally enveloped in the state’s claustrophobic grip. What’s particularly genius about it is that there’s an inexplicable numbness to it – the reader is utterly unable to pinpoint when they were folded into the story. There’s no sense of being fenced into fascism, instead it’s made to feel like an extension of the self. As if the parts of you that disappear are not truly gone because they remain with the state. Chilling.

I’d say The Memory Police is ultimately more a Bradburian novel than an Orwellian or Kafkaesque one. Ray Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451 in particular is thematically similar in its pursuit of absolute censorship and intrusive policing. Both novels also feature stolen moments of solace and connection, and suspenseful interrogations. Bradbury heightens these moments with punctuated alliteration whereas Ogawa leans into soundlessness, but they share intentions: to emphasise the enormity of loss under totalitarianism.

The two authors’ works reveal that, paradoxically, the path of total control ends at total nothingness. The “natural” end to a fascist society, when the violence (whether physical or psychological, or both) is taken to its final stage, is nonexistence. If resistance fails, the regime eventually destroys itself in the process of destroying its people and their history. There’s dark consolation in knowing that even if we don’t dismantle the totalitarian system, it’s fatal flaw is that it’s regressive in the most literal sense. What’s odd is that this idea doesn’t fill me with despair. Rather, it takes me to the conclusion that I can better justify why fascism isn’t the way forward.

I’m left curious about what this story would be like from the perspective of a soldier in the Memory Police, like Montag in Fahrenheit…

NOTE: I’ve shared my own ideas as well as those of the book club members – Prof Gina Neff, Stefanie Felsberger, Timothy Charleton, Christine Adams, and Tom Lacy – in this review.

Extra bits:

Other stories we thought of while discussing this one that you may also want to explore: Blindness by José Saramago, The Yellow Wallpaper by Charlotte Perkins Gilman, On Lying and Politics by Hannah Arendt, and The Diary of A Young Girl by Anne Frank.

I’m really pumped about exploring the absurd, surreal, and speculative with my colleagues and collating our insights here. We’ve limited our picks to fictional stories that are linked to tech futures and imagined societies. I'm a proponent of introducing fiction into the workplace, especially in policy spaces, as it encourages a different kind of thinking about our impact on the world.

Do you have a book club at work? This is your sign to start one! I’ll do a piece on how workplace book clubs enhance the culture at the end of the year.

See you next time,

- N